Marx’s Economics Revived

Introduction to Uno-Sekine Approach

Part II

[(6) How do you understand the current, world-wide economic crisis within the longue-durée history of capitalism? What, if any, are the potentials for social transformability that this crisis generates? What is called for to realize such potentials?]

6a) What is Uno’s view on the world economy after the war of 1914-17?

I have already referred to Uno’s considered view that the world economy after the war of 1914-17 does not define a new stage of capitalist development. To his 1970 definitive edition of Keizai Seisakuron (Economic Policies under Capitalism), which is widely regarded as the classical reference to his original idea of the stages-theory of capitalist development, he appended a short Memorandum containing some casual thoughts and observations on his thesis of “transition away from capitalism to another historical society” (let us call it his katokiron). This piece of work has, however, as much inspired as puzzled his followers. Most of the Japanese Unoists seem to follow the interpretation by Tsutomu Ôuchi (1918-2009), a junior colleague of Uno’s at the University of Tokyô, whose book entitled State-Monopoly Capitalism (1970) has been quite influential. It is true that there are some important points of agreement between Uno and Ôuchi. For instance, they both regard the adoption of the managed currency system by major nations, after their failure to restore the old system of the international gold standard, to have been an obvious sign of the beginning of the end of capitalism. They also consider that the involvement of the state in the nation’s economic affairs in the form of “inflationary labour policies” (by which they mean macro-economic policies aimed at a high level of employment and price stability) exceeds by far the confines of the typical trade policies of the imperialist state, such as cartel-inspired protective tariffs against dumping, which essentially served the key needs of finance-capital. However, I am certain that Uno would not have agreed with Ôuchi’s idea that the stage of imperialism, dominated by finance-capital, survived even after WWI into the so-called period of “state-monopoly capitalism”. Thus, even though, as generally believed, the latter period was a new phase of the “general crisis” of capitalism, and so could no longer retain its more vigorous pre-1914 “classical form”, Ôuchi nevertheless insisted that it essentially belonged to the age of “imperialism”, the final stage of capitalist development. But if so, the period of state-monopoly capitalism which began only after the October revolution of 1917 must also be regarded to be under the continued domination of finance-capital, even in its somewhat attenuated form. This view is diametrically opposed to Uno’s, which was that the stage of imperialism definitively ended with the war of 1914, the first and the last imperialist war, and that, with the demise of finance-capital, a new post-imperialist stage of capitalist development could not be defined. The trouble, however, is that Uno’s own argument on this point was by no means sufficiently convincing. Many of his followers, including myself, could not obtain a coherent enough picture of the world economy after Versailles according to Uno. Ôuchi’s State-Monopoly Capitalism tried to fill in the gap, in a rather eclectic fashion, by combining Uno’s stages-theoretic approach to capitalism with the prevalent and more conventional Marxist view on the world economy after the war of 1914-17. Perhaps, this makeshift solution was all that was possible at that time.

After a long search in the dark, however, I have recently felt enlightened on this matter by the works of Mitsuhiko Takumi (1935-2004) and Hyman Minsky (1919-1996). Takumi, after his extensive study on the World Depression of the 1930s, came to the conclusion that the crisis of 1929 in the United States could not be viewed as another “capitalist crisis”. This view is diametrically opposed to that of Ôuchi, who believed that it was just another capitalist crisis, and, as such did not lose its self-healing or recovery power, except that, because of its uncommon severity in the prevailing climate of the “general crisis of capitalism”, rather expeditious political interventions could not be avoided, and these were deemed to have inadvertently but decisively changed the future course of the world economy. Takumi’s view, in contrast, is that the crisis of 1929 initiated a deflationary spiral, involving a fall in the output and employment of leading industries. Normally, a capitalist crisis is followed by a sharp fall of product prices in the leading industrial branches, so that, for instance, in the stage of imperialism a crisis meant a catastrophic fall in the prices of such products as coal, iron and steel. Thus, while the low prices of these products persisted during the stagnation period, innovations were introduced in the method of producing them, which eventually enabled them to be produced at lower production-prices than before. That was sufficient to re-launch the reproduction-process of capitalism under a new system of values. Yet, there is no sign that this mechanism operated after the crisis of 1929. It is not that the prices of many important commodities (especially those of food and primary commodities) did not fall. They did, and catastrophically. What happened, however, was that, before these prices fell, the physical scale of operation (output and employment) of the leading industries shrank, because these were Fordist producers, meaning that their products had to be sold at rigid supply-prices equal to the unit-cost of these products suitably marked up.

After the First World War, the centre of commodity production shifted from Europe to the United States, where Fordist industry was becoming increasingly prominent. I use this term, Fordism, in the special sense of representing the “oligopolistic industry that (often) produces durable goods by means (always) of durable capital-assets”. In other words, the Fordist production embodies the Minskyian characteristic of crucially involving and depending on “durable capital-assets”. However, “the production of durable commodities by means of durable commodities” cannot be so easily operated in a capitalist-rational fashion, inasmuch as the “contradiction between value and use-values” can no longer be so easily surmounted. Both the laws of value and of population, the two basic laws that constitute the crux of capitalism, were, therefore, paralyzed; and so also was the self-recovery power of capitalist crisis. The intervention of the central (or federal) government in economic affairs became therefore unavoidable, and so what is now commonly termed the “mixed economy” with Minsky’s “Big Bank and Big Government” also became unavoidable features of the era. Uno himself as late as in 1970 did not seem to have quite grasped the nature of the changes that the world economy had undergone in these terms, given that he did not appear to have been well informed of the writings of Keynes or Kalecki. Yet, he must have viscerally felt the deep transformation of the world economy, during the interwar period and in particular following the Second World War. I believe that we must now squarely face the problem that Uno left behind, i.e., we must face up to the issue of what to make of the world economy after WWI. Uno broadly characterized it as essentially the phase of transition away from capitalism to another historical society. I call it the process of ex-capitalist transition, or of the disintegration of capitalism.

6b) How has the world economy evolved, in your view, since the Peace of Versailles?

In my view, this process passes through three periods. First, there is the interwar period of Great Transformation, here to borrow Karl Polanyi’s all too famous expression. WWI was the imperialist (and the first total) war, which in effect terminated the further stage-theoretic “development” of capitalism as such. Secondly, there comes the period, after WWII, of over a little more than three decades of Keynesian social-democracy, of which the first two, roughly the 1950s and 60s, materialized unprecedented prosperity under the relatively stable Pax Americana; but the last decade of the 1970s was plagued with “stagflation”. The third and last period of ex-capitalist transition began with the resurgence of neo-conservatism in the 1980s, which entailed the liberalization of finance. With the subsequent fall of the Soviet Union, the tendency towards the globalization of the world economy under U.S. hegemony confirmed and extended the dominance of finance over industry, not only in the United States but also worldwide through the deliberate globalization of the economy. This period still continues, but in an increasingly desperate fashion. I do not have time or space to review all these three periods in detail, but their minimal characterization is as follows.

The first period, that of the Great Transformation, was rather clearly divided into the decades of the 1920s and 1930s. During the first one, public opinion generally expected a return to “normalcy”, meaning the pre-1914 capitalist order based on the so-called “symmetric gold standard” (Temin), given that the vast majority was still unaware of the profound transmutation that the world economy had undergone due to the first total (all-out) war. As the illusion of a “return to normalcy” was shattered by the crisis of 1929 and the Great Depression of the 1930s which soon followed, the faltering bourgeois democracies found themselves besieged by the collectivisms of the right (fascism) and of the left (bolshevism). The world economy began to recover from the persistent doldrums of the Great Depression only when signs of the impending WWII had already become apparent. The second period was the era of the Cold War, in which the world was divided into the two opposing camps. In the West, the U.S. hegemony was unchallenged during the 1950s and 60s, though it quickly crumbled in the 1970s. It was also the new era of the “mixed economy” based on Keynes and petroleum. It worked well, in the first two decades, because “unit labour costs” were declining due not only to the increasing use of petroleum as energy, but also to the application of petro-chemistry, which enabled the replacement of natural fibers, resins and soaps with synthetic materials. If unit labour costs decline, the profit rate will increase for the same commodity-price, which should encourage private investment. In this climate, even a mild fiscal policy would work wonders, to the extent of realizing mass consumption and the affluent society. What happened in the 1970s was the reverse, as unit labour costs tended to rise, i.e., as money-wages were raised more rapidly than could be offset by the rising productivity of labour. Under those circumstances, a vigorous fiscal policy will not stimulate private investment, unless the prices of Fordist products are also raised. If there is cost-push inflation for whatever other causes, an expansionary fiscal policy will certainly exacerbate it. This in the main explains the persistence of stagflation in the 1970s.

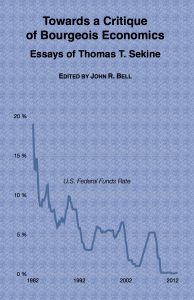

There was not enough time, however, for bourgeois economics to figure out why the stagflation could not then be so easily controlled, while many other unanticipated difficulties, both economic and political, arose one after another to shake the so far unchallenged U.S. hegemony in the West. The fear of American decadence vis-à-vis the Soviet Union which then still appeared implacable, coupled with the intellectual vacuum that paralyzed the economics profession, worked to the advantage of the financial interests congregating around Wall Street. They had long vegetated under severe regulations by virtue of the New Deal laws on banking, but had been reviving vigorously in international money markets, especially after the Oil Crisis of 1973. It was a golden opportunity for the financial interests to win back the lost territory inside the U.S. borders from the industrial interests, which, together with organized labour, had been the primary beneficiary of the Keynesian fiscal policies implemented in the context of the “mixed economy” that thrived after WWII. As President Carter’s office neared its anti-climactic end, the financial interests joined forces with the Chicago school to forcibly oust Keynes from macro-economics. First, monetarism was mobilized to control inflation, with a stringent squeeze on the increase of the money supply; then, Reaganomics, with its intense anti-union messages and policies ended by arresting the persistent rise in unit labour costs. But the price of the success in controlling inflation was the elevation of interest rates to an unprecedented level, which, in addition to mortally wounding the debt-ridden developing nations, also made it impossible for American commercial banks to abide by the legally restricted interest-rates which they could pay on time-deposits. Thus, the latter began to be withdrawn swiftly from banks to flee to other financial firms, which were prepared to pay a more reasonable reward to the lenders. When this regulation was finally lifted in 1983, a further de-regulation of finance was signaled. The A&M boom that soon followed made it clear that finance now called the tune, which industry had to follow. This heralded the coming-into-being of “casino capital”, which was to become the principal player in this third and last period of ex-capitalist transition.

6c) How do you characterize the current state of the world economy from your Unoist point of view?

The coming into being of casino capital is by far the most significant feature of the present-day world economy. Casino capital may also be understood to be the agent of the so-called “financialization” of the economy. It must, however, not be confused with finance-capital which in the past dominated the stage of imperialism. The theoretical foundation of finance-capital is interest-bearing capital, which explains the conversion into a commodity of capital itself or its “dualization”, that is to say, the separation of real capital in motion of the joint-stock (or corporate) capitalist enterprise from its fictitious form of equity shares capable of being traded piecemeal in the capital (securities)market. Whereas, in the pure theory, the trading of capital in the form of equity shares is strictly “notional”, it was actually practiced extensively in the stage of imperialism in the hands of finance-capital, as already pointed out. The reason was that investment in heavy industries was at that time far too costly for, or surpassed the resources of, individual capitalists, due to the “bulking-large of fixed capital” (to use Uno’s expression). It was then necessary to assemble as much investible funds available in society as possible within one company in order to convert them undivided into its real capital. The theoretical base of casino capital, however, is not interest-bearing capital, but the much more basic and primitive form of money-lending capital, which is sometimes characterized as an “irrational form of capital”. For, it can easily turn into loan-sharking and destroy the normal operation of sound capitalist enterprises. For instance, if it is allowed to collect interest higher than entrepreneurial profit, it can easily suffocate capitalist industry. It is for this reason that, in the theory of a purely capitalist society, the operation of money-lending capital as such is excluded, except as loan-capital, a form of differentiation of industrial capital itself, which makes the buying of commodities “on credit” possible. For, to the extent that the credit sale of commodities expedites the turnover of industrial capital, there will be room for loan-capital to contribute, if indirectly, towards the production of more surplus value (or disposable income) by industrial capital. Money-lending capital was quite active before the evolution of capitalism. Perhaps its main function was to hasten the dissolution of the old, pre-capitalist relations. Its reappearance in the new form of casino capital may well be an omen of the impending end of capitalism (in the sense of the capitalist mode of production) itself.

The return of money-lending capital in the form of casino capital suggests, first of all, that idle funds convertible into capital are no longer “scarce” as they used to be in the age of imperialism. However, we must always distinguish between existing idle funds in the form of monetary savings from out of already earned disposable incomes (or surplus value), and potential idle funds in the sense that, if I sold a commodity for cash now, it would then be saved by me and would have become idle money in my hands. Loan-capital converts the latter into active credit-money to buy commodities, the use of which expedites their circulation and thus enhances surplus-value production, i.e., enables more disposable incomes to be produced than in its absence. But, existing idle funds presuppose disposable incomes already earned, part of which may be saved instead of being spent (consumed). The savings, however, occur in the money form in the first instance, constituting existing idle funds convertible into capital (i.e., capable of being invested in real capital). It is important that these idle funds should be transformed into investment, or additional real capital, as soon as possible, that is to say within the same market period. For, failing that, the economy will necessarily turn deflationary, producing less incomes and employing less labour in the following period. But casino capital is, by definition, such that it seeks to profit from money games, which implies no intention of transforming the existing idle funds in its possession into real capital. Therefore, the more it profits in money games (i.e., speculative activities), the more it adds to the stock of existing idle funds inconvertible into capital (and hence incapable of producing real wealth). In other words, the more casino capital accumulates itself (by using high-risk-high-return “derivative commodities”, invented in the light of “financial engineering”), the more deflationary the economy will be, and the more impoverished will also be the society built on it. It, therefore, follows that there is not the slightest vestige of capitalist rationality left, rationality which follows from the true definition of capitalism by capital itself (or economic theory as it should be) in the present system of the world economy dominated by casino capital. Is not the latter anything else but the Grim Reaper of capitalism itself? Yet, according to the blind lesson of bourgeois economics today, which has ousted Keynes so as to be co-opted and sponsored by casino capital for staying in its service, we are made to believe that the contemporary economy is still “as capitalism should be”, i.e., the same “capitalism” that was once the dear old cradle of Western democracy, and which was supposed to combine “economic rationality” with “individual freedom”. That is most definitely no longer the case.

6d) How is casino capital related to the neo-conservatism promoted by Reaganomics and Thatcherism?

Casino capital came into being on the heels “neo-conservatism” which appeared for the first time towards the end of the 1970s, and its economic component spread vigorously thereafter in the forms of such doctrines as Reaganomics and Thatcherism. These professed the idea that “the smaller the government sector, the more revitalized the private-sector activities will be, and so (for some reason) the activities of the whole economy as well”. It also claimed that this goal would be achieved primarily by such measures as de-regulation and tax-cuts. The reason why these measures were so strongly campaigned for and put into practice then was that the empowerment of organized labour and the bureaucratization of industrial management had perhaps proceeded much too far in both the United States and Great Britain, and were thought to be primarily responsible for the slowdown of their national economies.

Neo-conservatism was a reaction against the welfare state, which had replaced the traditional bourgeois state by adopting the “mixed economy” in which the government sector spends at least about twenty percent of gross domestic expenditure (GDE) permanently. It is therefore necessary to review the evolution of the welfare state as it first arose and failed in the West in the early post-WWII years. During the interwar period, the conversion of the traditional bourgeois state into the new welfare state was not yet pursued in earnest, even though it was manifest that the traditional bourgeois state was no longer functioning adequately, especially in the 1930s. That was why the Western democracies, represented by Britain and the USA, found themselves besieged by the collectivisms of the right and the left, which eventually ended in the Second World War. Only after that catastrophe, and especially with the subsequent evolution of the Cold War, was the urgency of replacing the old bourgeois state by a new welfare state realized in the West. The reason was that, with the advent of the Soviet Union which undoubtedly exerted a powerful political and moral influence on labour movements around the world, the reproduction of labour-power could no longer be left to the automatic operation of the free labour-market. It was no longer convincing that the market could peacefully settle the conflicting interest between labour and capital. The Western democracies, in other words, had to face the “general crisis of capitalism”, by transforming the traditional “bourgeois state” into a novel “welfare state” in order to mitigate class struggles through the promotion of industrial peace. This new system which was reinforced in the West under the Cold War had, however, its own problems. In the United States where industrial peace was the primary concern, the system of so-called collective bargaining developed, supplemented by the programme of unemployment insurance; in Great Britain where public health and education were emphasized, the national health insurance that “cared for all citizens from cradle to grave” and equally comprehensive rules for the protection of labour were instituted with the express purpose of appeasing the working class. In the meantime, many large American firms remained under direct contracts with the Armed Forces, while the postwar Labour government in Britain nationalized a number of large firms in heavy industries and public utilities. Thus, in both Britain and the United States, the welfare state as a new type of the nation-state warmly protected labour and industry alike. All this amounted to the substitution of the prewar vestiges of the antiquated bourgeois state infested with open class struggles for the generous and munificent welfare state in Anglo-America. To the extent that the latter remained the leading industrial centre of the Western world during the Cold War, this reorientation of democratic societies was both apposite and judicious. Yet, it also had the negative aspect of over-protecting large corporations and organized labour which weakened competitiveness and tolerated indolence, leading to the complacency of both bureaucratized industry and unionized labour. Firms freed from insolvency and workers from unemployment on a near permanent basis need not be motivated to do any extra work to compete and excel. The inevitable consequence of that trend was the stagnancy of hitherto relatively free markets for commodity production and circulation. These symptoms became apparent as soon as industrial production recovered outside Anglo-America, as its products were increasingly exposed to severe international competition. Surely, these were not a “non-issue” to be lightly passed over, and a reactivation of the private sector in the mixed economy might well have been a viable tactic not to be dismissed off-hand either. As already mentioned, to the extent that a rising trend in unit labour costs was becoming manifest, a novel policy approach to reverse the trend so as to revitalize the economy was justifiably called for. Clearly, a rising trend in unit labour cost suggests a failure in the reproduction of labour-power as a commodity.

Yet the issue was not faced as a new challenge to democratic industrial society as such. The nature and the significance of the problem were not even vaguely understood. The solution was, therefore, sought blindly and offhandedly by, and to the benefit of, the powers that be. Neo-conservatism merely wished to retrieve the dear old image (now become thoroughly anachronistic) of a “vigorous and competitive capitalism” before the era of the Keynesian revolution, mainly by depriving the working classes of its newly acquired rights. It only recalled one-sidedly the good old capitalism now gone by, such as its inherent dynamism capable of withstanding “cut-throat competition”, “creative destruction” for innovations, “promotion of the burning work incentives”, “giving a chance to the will to succeed”, and the like. It even claimed that, only because capitalism was traditionally saddled with periodic crises and had to survive the regularly recurrent “hard times” in depression, during which competition in the market was bound to be intensified, that it taught both the entrepreneurs and the workers the disciplines of hard work for success, the will to compete for excellence, the individual responsibility of “self-help” and the like. It believed that only the survivors of hardships would be rewarded in the end with “individual successes”, while those who waited for the charity of the wealthy and dole-outs from the government would not. It was this kind of self-serving, retrospective hyperbole with regard to the exaggerated past glories and dewy eyed nostalgia for the grossly distorted image of capitalism of old, perfumed with due dozes of the Protestant ethics and Hayek, that inspired the neo-conservatism of Thatcher and Reagan. Yet, as biased as they indeed were, they nevertheless acquired the strong political and moral support of many within the middle classes. Not only did they both serve more than a single term of office, but they also left an enduring imprint in the psyche of the posterity. All this means that the issue that they faced was real. It was how, in a democratic industrial society, the reconversion of labour-power into a non-commodity ought to be handled. But such an issue, which puts the destiny of capitalism itself into question, far exceeded the resources at hand in the prevailing context, and could not even be discussed within the confines of neo-conservative discourse. In the meantime, if its solution had an apparent if temporary “success” by imposing some lacerating “shock therapies”, they left no lasting solution to the very problem that industrial society had to face. It was merely circumvented by repressing labour to counteract the rising trend of unit labour costs.

It was against this background that casino capital came to the fore. Neither Reaganomics nor Thatcherism which represented neo-conservatism were originally conceived as agents of casino capital. Yet, in hopes of controlling inflation and inspired by convenient passéisme, neo-conservatism adopted the truculent monetarist policy of squeezing the growth of the money supply, the consequence of which was to elevate the interest rates to a record-breaking height. As this invited the unanticipated plight of the commercial banks which quickly lost their time-deposits as I pointed out in the above, it became mandatory first to “liberalize the interest-rates which they could charge on their time-deposits” to protect themselves. It was this liberalization under force majeure that led to the more systematic “liberalization of finance”, which enabled the triumphant return of casino capital. What was called “liberalization of finance” in the United States was more colourfully renamed the “financial Big-Bang” in Great Britain. In both cases, it meant the takeover of economic power by the financial interests (casino capital) from the industrial interests (the coalition of the managerial class and organized labour). Industrial society thus became a gambling society. Furthermore, this shift of economic power occurred at just about the right moment, when the Cold War was winding down, which went a long way towards reconfirming and completing the sway of both Reaganomics and Thatcherism. For, it was ultimately the threat of communism that had inspired the age of Keynes and social democracy. Thus, when the Soviet Union disintegrated, the unknowing Western media cheerfully frolicked over the “victory of capitalism over socialism”. But when the trumpet sounded its “victory”, capitalism ironically entered the terminal phase of its disintegration, and I am afraid precipitously, as Minsky’s “financial instability hypothesis” was about to follow an explosive path to its end with a resounding crescendo, as the economic system sought to function as if its ultimate dependence on the reproduction of labour-power could be entirely ignored.

[(7) In reviewing the process of the “disintegration of capitalism” above, you have referred in passing to the evolution of bourgeois economics during that process. The prevailing opinion today, however, is that bourgeois economics has somehow attained paradigmatic legitimacy and has as well been “naturalized” as an “objective science, however imperfect”. Such a view seems to be reinforced in the 1980s after the neoclassical resurgence and the ejection of Keynes especially after the end of the Cold War. How do you account for such development in bourgeois economics?]

7a) Will you describe how bourgeois economics fared in the first two periods of ex-capitalist transition, i.e., during the interwar period and the period after the Second World War for about 30 years, prior to the so-called neoclassical counter-revolution?

I have already described the development of neoclassical economics during the forty years spanning the Franco-Prussian War and WWI. During that period, however, it was not only the neoclassical school with its Parnassian stance that was influential. The more practically-oriented, German late historical school, led by Gustav Schmoller, with greater emphasis on economic policies (which it called Sozialpolitik generically) than on economic theory, was equally important and powerful if not more so, especially in such late-developing capitalist nations as Germany and Japan. However, the influence of that school quickly waned after the defeat of Austria and Germany in WWI, leaving the neoclassical school as apparently the only legitimate (or perhaps better bona fide) heir to mainstream economics. The sudden rise in the international scene of the United States, where the neoclassical school had been (through Marshall) encroaching upon the indigenous school of institutionalism (represented by Veblen, Commons and Mitchell), also clinched that impression. Neoclassical economics, however, inherited from its classical predecessor the complete neglect of the analysis of money in the economy, which made it blind to the reason why, despite the pious wish then almost universally shared for the restoration of the international gold standard, that project was doomed to fail.

Thus, in the absence of a credible advice, the political leaders of the time relied on their practical hunch and conventional wisdom in seeking a “return to gold” to no avail, which only magnified the deflationary trend already present inasmuch as they only had in mind the return to gold at the prewar parity. Then, there came the Great Depression of the 1930s which aborted all hopes of returning to gold, and the real cause of which no neoclassical economist could understand or adequately explain. As real economic life visibly deteriorated, disenchantment with capitalism, liberalism and democracy led to their being suddenly besieged and threatened by totalitarianisms of the right (fascism) and of the left (bolshevism), as I more than once pointed out above. Compelled by the circumstances, President Roosevelt opted in 1933 for the “New Deal” in the United States, which confirmed the unavoidability of economic intervention by the state (i.e., federal or central government) even in times of peace. Keynes’ economic thought was not yet well known; but a large number of American economists went to Washington to assist the New Dealers. This made economics a credible profession, in addition to being a key subject of in-depth academic study in universities, for the first time in history. Soon afterwards however, with the outbreak of the war in Europe, the Great Depression quickly faded away as the United States adapted its economy for war.

By the time WWII ended, the United States, which had risen to an unchallenged pre-eminence in the world economy, adopted the Employment Act of 1946, and this latter stipulated that it devolved on the federal government to ensure a high level of employment and stability of prices in the nation’s economy. Keynes had authored his General Theory in 1936, but at first it only baffled his neoclassical colleagues in Cambridge and Whitehall who could not see its real import. Only his students with more open mind could sense the revolutionary character of the book. Among them were two young Canadians (L. Tarshis and R. Bryce) who brought their teacher’s ideas to Harvard where, in view of its earlier exposure to the New Deal, Keynes was increasingly accepted. Elsewhere in the United States, however, the mood was much more hostile to Keynes; thus, he was frequently and casually stigmatized as a covert communist. The ideas (1) that the national economy of the day could no longer be run by the private sector alone, since, in the aggregate and ex ante, its savings were liable to exceed investment, and (2) that the government sector must routinely stand ready to compensate for that deficit in private spending, in order to prevent the economy as a whole from sliding into a bottomless deflation, were diametrically opposed if not held thoroughly revolting to the liberal (and neoclassical) creed. For, according to the latter, the Invisible Hand of Providence should always be trusted to lead the market to a pre-established harmony of conflicting interests. Such ideas as contravened this creed were, of course, much too “socialist” for the right-thinking American conservatives to countenance. However, the fear that, when the war ended and wartime measures were dismantled, a great depression might return to wreak havoc in the economy was also real and menacing. Thus, over the ten years that separated the publication of the General Theory and the Employment Act of 1946, America was divided between pro- and anti-Keynesians. The disagreement between them, however, had to be resolved willy-nilly in favour of the former, as the United States emerged from the war as the sole leading economic power, with its territory and productive capacity virtually unscathed by wartime devastations. Given this fact, Washington had to find ways to live with the Soviet Union, its ideological enemy and former ally. For, a simple return to the prewar regime of the bourgeois state, where class struggles would be intensified, would only abet the infiltration of communism into America, which was an impossible option. It was, therefore, necessary to stabilize American society by seeking industrial peace and class harmony along the New Deal lines. Not only was the stabilization of society necessary to rearrange postwar domestic conditions, it was also mandatory as part of the U.S. international strategy, especially after the onset of the Cold War. Presumably for this reason, the Employment Act which endorsed fiscal Keynesianism was adopted. As a matter of fact, that strategy soon turned out to be far more successful than was initially anticipated. The reason for that happy outcome was the radical “petrolification” of traffic and industry, as it was perfectly adapted for the rebuilding of a new peace-time economy, while raising the productivity of labour dramatically.

As already mentioned, the prevailing opinion during the 1920s was that a recovery of the pre-WWI “capitalist order”, together with the restoration of the smooth operation of the “symmetric” international gold-standard system was the best possible outcome. The unfortunate fact that the impossibility of this dream was not realized until the fateful crisis of 1929 made the Great Depression of the 1930s unavoidable. As the real economic life of society visibly deteriorated everywhere, doubts arose with regard to the efficacy of “capitalism” itself and the bourgeois-liberal democracy which represented it, until these were besieged by the collectivisms of the right and the left. The one on the right (represented by Japan and Nazi Germany) adopted an aggressive military stance, intent upon destroying the established capitalist nations with imperialist advantages, while the one on the left (represented by the Stalinist Soviet Union) was no less determined to put an end to capitalism and bourgeois democracy in favour of “socialism” and “the dictatorship of the proletariat”, garbed as a “people’s” democracy. The only option available then for the bourgeois democracies to survive was to reluctantly ally with the Soviets in the first instance to eradicate the more impending threat of the right-wing collectivism (represented by the Axis powers). This meant, however, that, as soon as the war ended in the victory of the Allies, an East-West confrontation leading eventually to the Cold War was unavoidable. Under such circumstances, it became both necessary and urgent for the Western camp to convincingly affirm and broadcast the superiority of its own regime in contrast to that of the “Eastern Camp”. Specifically, it meant that “capitalism” even if in a “modified” form, which still depended largely on the working of the free market for commodity-production, was better (meaning, more conducive to democracy and freedom) than totalitarian communism, an economy which had to be centrally planned by the state’s command. As already repeated, the so-called “capitalism” in this context was already in its process of disintegration, so that the “mixed economy” with substantial macro-economic interventions of the central state (which Marxists used to call rather incongruously state-monopoly capitalism) had to be accepted. Yet it was still felt far more congenial to and acceptable by the majority of the population in the West than the command-economy under socialism.

At this point, bourgeois economics (at the helm of all the other social sciences) was entrusted with the new mission of upholding this “modified capitalism” as superior to any other way of organizing the real economic life of society. The role of the ideological superstructure in all societies is to endorse, justify and promote the ruling hierarchy and vested interests of the existing society in one way or another. For, otherwise, society is liable to be infested with discord, ruptures and instabilities and could not be held together peacefully. Thus, for instance, in medieval Europe, Catholic Church tried to teach its religious cosmology which was believed to be the key to the integrity and stability of society, and so, that cosmology was inculcated at all levels, with perhaps the “natural theology” of Saint Thomas Aquinas reigning at its intellectual pinnacle. In the far more secularly-oriented contemporary age, where the (natural) scientific view of the world prevails, “economics” is meant to play the same (or at any rate similar) role, since it, of all the social sciences, appears to be the most credible, in the sense of being the closest to the natural sciences (and hence believed to be “objective” in some sense). I have referred to the mathematization of economic theory during the forty years preceding WWI; but, at that time, it was marginal (or infinitesimal) calculus that was central in that process. During WWII, however, economics learned from so-called Operational Research somewhat more sophisticated and powerful techniques in linear algebra, which were thought especially attuned to the study of the inter-industry analysis pioneered by W. Leontief, but which turned out to be applicable far more widely to many micro-economic theoretical issues. On the other hand, together with the adoption of macro-economic models inspired by Keynes, the collection and preparation of national-accounts statistics also made giant strides to the extent of entailing a proliferation of econometric studies as well. Under the circumstances, economics appeared to be increasingly “naturalized” in the sense of becoming as “objective” as natural science, as if to ignore the plain fact that a “natural science of society” would be by far the most preposterous oxymoron.

After the sputnik crisis of 1957, a new era of advanced mass education dawned in the United States and elsewhere in the West, and university curriculums were overhauled with a view to training Western youths to be capable of competing favourably with their counterparts in the Soviet camp. In economics, the so-called “neoclassical synthesis” popularized by Paul Samuelson became the main recipe to be taught systematically in Western universities and business schools, in order to inculcate the superiority of the Western democracies over the Soviet system in the minds of youths (especially of the bright, ambitious and upwardly-mobile ones, who could be easily recruited in future to be convinced spokespersons, direct or indirect, of the bourgeois-liberal ideology). Over generations, this has created a large population of “professional” economists, well grounded in neoclassical price theory and some Keynesian macro policy models. But this neoclassical “synthesis” was only a limited and half-hearted adoption of Keynes’ “multiplier concept” as macroeconomic income theory, ignoring almost totally the more subtle “uncertainty theory of investment” and “liquidity preference theory of money”, which constituted the crux of Keynes’ novelty. Besides, it was in no sense a genuine “synthesis”, since a thick wall remained between the micro price theory and the macro income theory that could never be crossed from one side to the other. For instance, no one could logically relate the macro-economic multiplier (the reciprocal of the propensity to save) with the micro-economic” price-consumption curve” derived from the familiar utility maximization of the individual under a budget constraint (which, of course, allows no saving out of income). This means that the much touted “micro foundation of macro theory” could amount to no more than a hollow battle cry. For how can the micro theory which permits no saving by the individual consumer serve as the foundation of the macro theory which routinely talks of savings-investment connections? In the dialectic of capital, by the way, it is the macro-law of population that determines the value of labour-power, thus providing a solid foundation for the micro-law of value that determines general equilibrium prices, and hence values (homogeneous labour directly or indirectly allocated to the production) of all other commodities, given the value of labour-power.

7b) Why was the faith in the “neoclassical synthesis” within bourgeois economics so short-lived, and how was it that it came to be replaced by the “neoclassical counter-revolution” of the 1980s in particular?

Up to the middle of the 1960s, economics of the “neoclassical synthesis” reigned as a highly credible new knowledge (conceivably as prestigious as the “natural theology” that prevailed in the late mediaeval age), despite its methodological fragility and shakiness as mentioned above. For one thing, the economists had to learn many new techniques, mostly quantitative, to respond to the new role assigned to their profession. They, therefore, had to devote their attention to more urgent and practical problems, and did not have time to worry about deeper and more sophisticated, methodological speculations. For another, it appeared as though they were quite successful in “prescribing” proper economic policies in the new context of the “mixed economy”, since the transition from the wartime to peacetime economy appeared to proceed rather smoothly. The great productivity of the “petrolified” new economy could respond to the voracious appetite for ordinary means of livelihood, the demand for which had long been suppressed in deference to wartime priorities. But the halcyon days of bourgeois economics thus reformulated under the Pax Americana did not last very long. There were a few basic reasons for that grievous turnaround.

First, the burden of military spending by Washington, at home and abroad, in order to defend the whole of the Western Camp during the Cold War was becoming increasingly onerous to America, and undermined its industrial advantage which had been remarkable in the early postwar years. As European and Japanese industry recovered, and as their products began to compete in world markets with their American counterparts, the latter were put on the defensive, which first led to an increasingly lackluster performance in the U.S. balance of payments, and subsequently led to the dollar crises in the 1960s. By the end of the decade, the United States was no longer capable of defending the so-called Bretton-Woods IMF system, which was basically a gold-exchange standard that hinged upon the fully credible American dollar. Secondly, the vigorous elevation in the productivity of labour due to the overall “petrolification” of the postwar U.S economy more or less ran out of steam in the course of two decades or so. Although the oil industry in the United States developed early in the imperialist era, it was not until the invention of the internal combustion engine, and subsequent improvements of it, that the real worth of oil as an efficient converter of heat into mechanical energy was widely recognized. It was for that reason that, up to the end of WWI, the main energy source that fuelled capitalism was incontestably coal and not oil. Yet, WWII changed the whole perspective regarding this matter, as it demonstrated the great advantage of oil over coal not only in carrying out warfare but also in rendering civilian life more comfortable and affluent. It also turned out that petro-chemistry could produce such synthetic materials as could effectively replace natural fiber, resin and soap, the supply of which had been limited. The tremendous rise in labour productivity that radically benefited U.S. industry in the first instance after the war was beginning to be exhausted towards the end of the 1960s. Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, the “euthanasia of the rentiers” that Keynes had hoped for, not only failed to materialize, but its reverse (i.e., their vigorous return) in the 1970s also put an end to the Keynesian revolution. New Deal legislation in the 1930s had provided a strict distinction between commercial banking and other forms of financial operation, so as to avoid the former (which tended to be less lucrative) to be poisoned by speculative activities (which were riskier but promising higher returns). However, as euro-dollar markets developed early in post-WWII years, American banks increasingly shifted their activities offshore to circumvent regulations restricting them at home. Soon after President Nixon’s accession to the office, two critical events followed: the first was the end of the so-called external convertibility of the US dollar into gold, which suspended the Bretton-Woods IMF regime and opened the way for the demonetization of gold and the universal adoption of flexible exchange rates; the second was the Oil Crisis of 1973, which, by tripling the price of crude oil overnight, introduced a decade of “stagflation”.

Perhaps, Walter Heller’s book, New Dimensions of Political Economy, 1966, symbolized the acme of American fiscal Keynesianism. Heller was advisor to President Kennedy and the book was published before the Tet Offensive in the Vietnam War, and so it was full of self-confidence, which suggested that the economists had by then fully learned the arts and skills of macro-economic control of the national economy, and that to the extent of being capable of “fine tuning” it. Yet, ironically, it was from about this date that a series of events struck exposing the decline of U.S. industrial hegemony and in the process shaking the self-confidence of bourgeois economists. The cause of the so-called “stagflation” that ruled the 1970s was by no means simple. It appeared to begin with an international rise in the prices of primary commodities (food and industrial raw materials), which culminated in the explosion of the price of crude-oil through the agency of the OPEC cartel. Moreover, that came on the heels of the collapse of the Smithonian agreement, with which Nixon had hoped to redress the existing IMF regime to America’s advantage. This meant the end of the gold-exchange standard built on the full credibility of the U.S. dollar, and that event unleashed a universal adoption of freely floating exchange rates. When by that time cost-push inflation on the supply side became rampant, even while the economy stagnated at a low level of employment due to weakness on the demand side, Keynesian economists did not know what to do. Money wages having risen more promptly than labour productivity, unit labour costs rose universally. It meant that the Heller-type fiscal Keynesianism would not only be powerless but would also make things even worse by feeding on the inflationary pressure. Thus, the so far unquestioned prestige of Keynes understandably plummeted, giving way to monetarism as promoted and popularized by Milton Friedman, with the clarion call that “inflation was a monetary phenomenon”. This statement in itself was surely not false, but the only monetary theory that classical and neoclassical economics were cognizant of was the quantity theory of money for which money remained no more than a neutral “veil” of the real economy, which could therefore be “dichotomized” from the monetary economy. The great failing of contemporary macroeconomics with its obvious anti-Keynesian flavour lies in the fact that, while ostensibly introducing money into its paradigm, it completely fails to understand the real meaning and function of money in the economy.

7c) Why did “neoclassical counter-revolution” of the 1980s occur to bourgeois economics, and what, in your view, was its significance?

After the 1980s, with the resurgence of conservatism in America, the mainstream economics curriculum in leading universities gradually dropped the Keynesian content and became overwhelmingly “neoclassical”. As already stated, neoclassical economics is technically advanced in mathematical skills; but, content-wise, it is impoverished in that it has degenerated into an ideological apologetic of a “capitalism” that must be constantly updated, modified, revised or whatever, in the sense of being redefined to suit opportunistically and arbitrarily the hierarchy and vested interests within the existing society. What I mean by this is the following. If the “capitalism” to be defended in order to keep the Soviet threat at bay is something that would benefit a social- democratic coalition of industrial managers and organized labour, Keynesian economics (which calls for the “euthanasia of the rentiers”) will be most convenient and welcome; but, if another version of “capitalism” must be defended that promotes unmitigated freelance gambling and near-theft in financial markets, so as to assure a maximum freedom to casino operators, there is clearly no place for the continued presence of Keynes in the economics curriculum of prestigious educational institutions. Indeed, what made the neoclassical “counter-revolution” necessary in the 1980s in economics was that the guardian of the existing form of “capitalism” changed from industrial management in coalition with organized labour to the rule of more autonomous (in the sense of more self-sufficient) money-gamers, or, in short, the shift of power from the industrial to financial interests (from Main Street to Wall Street), first in the United States and then, through globalization, to the rest of the world. This process of a power shift (or a counter-managerial revolution accompanied by the sudden rediscovery in America that corporate firms belonged to the shareholders, not to the managers and other stake-holders) was again by no means simple and straightforward, since many complex factors were involved in it.

After the Oil Crisis, as frustrations mounted at home as fiscal Keynesianism seemed unable to cope with persistent “stagflation”, offshore American banks proved their remarkable prowess in the recycling of oil money with an agility and efficiency that no conceivable official channel that would require inter-governmental co-ordination and agreements could have hoped to accomplish. This gave great confidence to the financial interests nestled in Wall Street, which then swore to retrieve the territory lost to the industrial interests during the long period of sway by the New Deal and Keynesianism. By the end of the Carter administration, Paul Volcker’s tough (and apparently monetarism-inspired) Federal Reserve policy was introduced to arrest inflation, which, to the extent that it was successful, elevated interest rates to an unprecedented height, thus causing two unanticipated but serious and problems, as I have already remarked. One led to the “debt crisis” in which many developing countries were caught and ruined, and the other to the massive exodus of time-deposits from commercial banks to non-bank financial operators. By that time, the new Thatcher-Reagan era had arrived with the anti-Keynesian banner of “supply-side economics”. The keywords were “de-regulation and small government”, with the precept that “the smaller the government the more reactivated the private-sector economy would be”. Organized labour was also under pressure to abandon its many previously acquired rights in order to become more exposed to the “disciplines of the market”. In consequence, the rising trend in unit labour costs was arrested, which, in effect, rendered Reagan’s (military) Keynesian policy quite successful, though this point was never openly admitted. The plight of depository institutions (including commercial banks) led, in the first instance, to the de-regulation of interest-rate on savings deposits; but that entailed a more general and systematic de-regulation of finance, putting an end to the “euthanasia of the rentiers” and hence also to Keynesian economics. Behind this vigorous resurgence of economic neo-conservatism in Anglo-America and its propagation to the rest of the world through the policy of globalization lay the gradual extinction of the Soviet Union and the winding-down of the Cold War.

In the heyday of the neoclassical synthesis, it was generally thought that macro- economic “income theory” was Keynesian, while micro-economic “price theory” remained classical. Perhaps Milton Friedman was an outstanding exception in claiming all along the legitimacy of neoclassical macro-economics, based on the quantity theory of money. His timely fame and teaching were enthusiastically acclaimed by the younger generation of economists clustering around the University of Chicago. The fact that macroeconomic models no longer needed to abide by the constancy of the price-level opened the door to many innovations in the field, and that was rather “timely” as “game-theoretic” thinking suddenly caught the fancy of economists and quickly permeated the field of price theory, the micro component of economics. Contrary to the traditional belief, the application of the idea of “non-cooperative games” among a finite number of players to the theory of market exchanges had, by then, shown that its general solution (called Nash equilibrium) was not Pareto-optimal (meaning that no one can be made better off without making someone else’s worse off), as can be readily seen through the celebrated example of the so-called Prisoners’ Dilemma. From this point of view, the traditional theorem guaranteeing that a competitive equilibrium of the Walrasian system would be Pareto-optimal turned out to be valid only when the number of traders in the market was deemed to be infinite, a special and limiting case of Nash equilibrium. In other words, the application of infinitesimal calculus to the economic theory of general equilibrium is reasonable only when the capitalist economy approaches its pure image at the limit. When the actual capitalist economy is more likely represented by the oligopolistic markets of interacting firms, it is hard to stick to a price theory that is based on the assumption that individuals and firms operate by “taking” the prevailing market prices to be given and unchangeable by them, and simply adapting to those parameters. For, under oligopoly, the market participants are quite aware of the fact that their own action will entail mini-max adaptations among their small number of main competitors. As soon as such a game-theoretic situation is presupposed in the market, the end result is never Pareto-optimal, meaning that the market does not optimally allocate resources, the upshot of which is that contemporary “capitalism” (or capitalism in disintegration to be more precise) is not in general led by the Invisible Hand of Providence to the much flaunted pre-established harmony of conflicting interests. If so, however, micro-economic price theory cannot be counted upon to demonstrate the eternal virtue of capitalism. The reason why the Chicago economists today are so eager to produce non-Keynesian macro-economic models inspired by the so-called “rational expectations hypothesis” is that it will in their vain hope somehow serve as an adequate substitute for the Invisible Hand.

7d) Given your view on the current state of bourgeois economics, what do you think of the prevailing opinion today that it has attained “paradigmatic legitimacy” in that it has been successfully “naturalized as objective science, however, imperfect”?

I would like you to understand that the whole idea of “naturalizing” economics, or any other knowledge of society for that matter, in order to pretend that it can become “objective” in the same sense that natural science is objective, is a complete joke. Not only is such an idea preposterous in the extreme, but it is also impossible. Yet, so many great pundits of bourgeois economics, from Samuelson to Friedman, claim in unison that there is only one way to arrive at scientific (i.e., objective) truth, and that the economist must seek truth in the same way as the physicist does. That view is also widely shared, believe it or not, by many Marxists! In the study of scientific method, that position is known as “reductionism” and it is a false and misguided idea, as I have already stated many times. It is important to understand that human society (which we ourselves create, whether consciously or unconsciously) and nature (which stands out there and over against us, as ready-made by some power beyond us) are two entirely different objects of study, and so must require different methods of inquiry to arrive at their truths. Even the meaning of “truth” (or of the objectivity of knowledge) that we seek in each case cannot be the same. First of all, nature is never known to us totally, since it is not our own creation. Our knowledge of nature is bound to be “partial and presumptive (tentative)”; and so it must be stated in a “predictive, prescriptive and prospective” form. The knowledge of our own society, in contrast, is not so, because we ourselves create (organize and form) society, so that, if the knowledge of society is not “total and definitive”, that is to say, if we do not understand the thing-in-itself of society, it would be meaningless. In other words, unlike nature, society is never given to us from the outside, irrevocably and forever. Therefore, we have the right to reform, redesign and reorganize (i.e., revolutionize) our society, so as to creatively improve upon it. We can do that, however, only so long as we can work on its economic substructure, that is to say, so long as material (i.e., use-value) conditions evolve in such a way as to permit us to do so. The question is whether we can confirm that these conditions are objectively present or not. Such knowledge most certainly cannot remain just “partial and presumptive”; it must be “total and definitive”.

I have already stated above that the knowledge of our own historical experience is “grey” in Hegel’s sense, meaning that it has to be the knowledge of ourselves in the past (and by extension also in the present insofar as it is where the past necessarily led us). Our self-knowledge must be “post-dictive, descriptive and retrospective” because we cannot change our own past. It is for that reason that, unlike the knowledge of nature, our historical knowledge cannot be technically made use of. Only the “partial and presumptive” knowledge of nature permits us to utilize it in “technical applications” so as to enable us to conform to, or to “piggyback” on, it prudently, because the laws of nature operate on their own and essentially beyond our control and scruples. This fact does not mean that we should forget about the knowledge of society, such as economics, which refuses to be used instrumentally for smart-alecky “policy prescriptions” or in petty “piecemeal social engineering” à la Popper. For that would be prohibiting us from being enlightened by our collective self-knowledge, and thus committing us to remain animal-like (rather than fully human) beings. It is, moreover, important to recall that, only with the dawn of the modern age, did social science, and economics in particular, emerge as the study of capitalism, as a systematic body of knowledge. This means that, for the first time in history, humankind has been given a chance to know itself collectively in society. For, only when the economic substructure of modern (capitalist) society is fully known by economics, do we learn for the first time what we are and what we do in it, and, by extension (or in comparison), in other human societies as well. Put otherwise, the discovery of economics, concomitant with the evolution of capitalism, gave us the first chance to know ourselves in society (i.e., as social beings). But, capitalism comes into being only when material or objective (i.e., use-value) conditions for its existence become ready; it passes away when these conditions are no longer present. Although ideological (or religious) faith has a role to play in the evolution of capitalism, it does not determine its existence. It only works as a positive or negative catalyst in either expediting or delaying the necessary temporality of capitalism.

In the light of these reflections, it is simply unbelievable to me that the leading pundits of bourgeois economics are all so naïve and ingenuous (school-boyish) as to be duped by the evidently false (though superficially plausible) thesis of “reductionism”, and to thus in effect lose sight of what they are themselves doing in reality. Surely, there must be several explanations for this singular phenomenon. The most plausible one of them in the present vulgar age may, however, be that they were so brilliant and could learn the existing paradigm of bourgeois economics so quickly as to become quite young established authorities in the profession, which thereafter treated them very warmly, until they felt not only obliged but comfortable to defend rather than to critique it. In other words, they never really had a chance to reflect on what they actually do by becoming pundits of bourgeois economics, before they were caught and co-opted by the paradigm to become its mouth-pieces. I have been at pains to claim that, unlike economics in the Marx-Uno tradition, its bourgeois version has a role to play as the natural theology of capital. It is essentially an incantation in praise of the hierarchy and the vested interests of the present society which they want (unknowingly if innocently) to defend and perpetuate at all costs (that is, even when the use-value conditions no longer warrant the litany of “capitalism forever”). Undoubtedly the establishment is very eager to recruit such brilliant teachers as Samuelson and Friedman by lavishing on them all the worldly fame, praise and honour for their signal service of exalting this society, which, at present, is dominated by casino capital, and thus ideologically supporting it. Recall the serious hazard of approaching economics without taking a due antidote in advance! For, one gets so easily infected by the virus of bourgeois-liberal ideology as soon as one begins to learn about the pre-established harmony of the market, and feel empowered to play its tune (even though anything approaching it departed this world a long time ago). Marx was a very rare exception to the rule for having been impervious to that ideological indoctrination, as I pointed out earlier. But if Marx’s immortal work in economics is not apprehended in its full worth along the Unoist line, but trivialized instead as a mere weapon of his anti-bourgeois ideological campaign, that would only reinforce and perpetuate the “paradigmatic legitimacy” of a false economics.

Economics is a dangerous subject. For, in order to become adept in its paradigm one has to learn the rules of its game, which implies how to think “capitalist-rationally”. By the time one has learned to be capitalist-rational, however, it becomes difficult to realize the confines within which that rationality remains valid. The capitalist management of the real economy is rational, when and only when the most important and prevailing use-values of the real economy are more easily producible “as commodities” than otherwise. This is the point that bourgeois economics is determined to forget, and so never teaches; unlike the dialectic of capital, it fails to take the “contradiction between value and use-values” seriously. This means that it cannot really know what capitalism is all about; it can only worship (and believe in) capitalism, even when the latter is widely out of the right context. In other words, bourgeois economics is a religion and not science. As such it will defend “capitalism” (which may be as arbitrarily and opportunistically redefined to suit its present purpose), even when capitalism is in disintegration, having already completed its historical mission (or raison d’être). Even now, when capitalism is already in transition to another historical society, bourgeois economics remains determined to answer the siren call of “capitalism forever”. Such claims as “naturalized social science”, “paradigmatic legitimacy” and what not, are just parts of the smokescreen behind which to hide its true emptiness and false intention.

[(8) You seem to be saying that bourgeois economics is in effect wholly bankrupt, so that it cannot offer any viable solution to the present economic crisis which is tormenting the world economy today. In what way can we control the tyranny of casino capital and liberate ourselves from it? Can that be done within the scope of capitalism and bourgeois economics?]

8a) On what ground do you claim that bourgeois economics is incapable of saving capitalism? What is wrong with that approach and with capitalism in your view?

I have already pointed out that bourgeois economics ignores the fact that capitalism consists of a temporary and uncertain union of the real-economic life of society (which must exist in one way or another in all societies) and its commodity-economic or mercantile management (which is historically unique to capitalism). That is to say, it fails to recognize the contradiction between value and use-value, the overcoming or surmounting of which generates (gives rise to) capitalism. This thesis implies that the two sides are not always meant to merge or blend into one, since they are different; yet, under special circumstances, they do accommodate each other to enable capitalism to exist. Those special circumstances occur when the side of real economic life (represented by use-values) does not raise too dogged resistance against the side of its mercantile management by capital (represented by value), of which the limiting case is when the use-values are just “nominal”. This is the case of a “purely capitalist society” which the dialectic of capital (or abstract economic theory of capitalism) presupposes. Such a society, of course, does not and cannot factually exist, yet it is nevertheless not a mere figment of the imagination. For, it is the real abstraction on the part of capitalism to actually purify itself in history that enables us to envisage such a society as a limiting point. It is only in this way that the once-for-all and historically transient institution of capitalism can be theorized, in the sense that its inner logic (or operational “software”) can be brought out into the open, as the dialectic of capital. Unable to comprehend this crucial point, bourgeois economics naïvely believes that an “instrumentalist” economic theory (which lends itself to our technical application) can be formulated in terms of the axiomatic method of tautological logic (as in mathematics and its applications to natural science). That would imply that bourgeois economic theory is expected to apply to any use-value space with equal validity. What used to be valid in the age of cotton should, in that case, remain so in the age of steel, and even in the era of Fordism, in which complex use-values are produced with sophisticated engineering as embodied in Mynskian “durable capital-assets”, that is, in what we may today call “plants and equipment”. This is quite different and must be distinguished from producing simpler use-values (be it wool, cotton or steel goods) with “tools and machines”. In other words, the historical dimension and evolution of capitalism is entirely ignored in the bourgeois discourse. This, however, follows from the application of the formally-logical (that is, necessarily axiomatic and tautological) method to formulate economic theory, which is supposed to be valid in all conceivable use-value spaces. In this way, it is clearly impossible to apprehend the present state of “capitalism” in a historical light, that is, from the point of view of evolving use-values.

Capitalism developed in the three stages of mercantilism, liberalism and imperialism, in which wool, cotton and steel were, respectively, the types of use-values that prevailed. Even in the process of its disintegration, capitalism (which has remained in its imperfect form to the extent that commodity production has survived) is undergoing significant changes, reflecting the rather precipitous evolution of the use-value spaces which can easily exceed the mercantile management of capital. For example, the present phase of ex-capitalist transition characterized by the dominance of casino capital would be unthinkable but for the prior development of the information-and- communications technology (ICT), which blends the production of commodities with artificial intelligence capable of sorting out information and communicating it. The advance of our life and industry, in consequence, is surely revolutionary and spectacular, though, in its wake, it also entails many such unwelcome and annoying problems as “hacking”, “cyber-attacks”, “cyber-crimes” “massive information leaks to offend privacy” and the like, which are difficult to control. When capitalism is in the process of its disintegration, the use-value space tends to diverge increasingly from that which it should ideally stand on. If this basic concept is ignored and if therefore we expect capitalism to be always present (if in states of imperfection) and securely so regardless of the evolving use-value condition as believed by bourgeois economics, it is a far cry to actually identify and comprehend the real state of things: a world economy in the throes of a systemic crisis today.

At present, capitalism is in the final phase of its process of disintegration. I have already suggested that this process evolves through three phases: the interwar period of the Great Transformation, the immediate post-WWII period of Keynesian social democracy and the most recent and final phase, which is dominated by neo-conservatism and casino capital. The present crisis of the world economy which dates from the fall of Lehman Brothers (in 2008) forebodes the end of an already disintegrating capitalism. In other words, when the present crisis is surmounted, a new historical society which will eventually replace capitalism (and which for convenience may be referred to as “socialism”, though no one knows as yet in full detail what it will eventually involve) must have already begun its formation. If so, there are already a few signs of capitalism’s demise that ought not be carelessly overlooked or dismissed as less than significant. The first thing that strikes me is that the present system under the domination of casino capital has no inherent tendency to seek capitalist rationality. It does not seek a maximum production of surplus value (or of the “disposable income” in the bourgeois terminology), but only maximizes the expropriatory gains accruing to the more powerful of casino capitals. In other words, it does not lead to a Walrasian general equilibrium which is Pareto-optimal, but to a Nash equilibrium of non-cooperative games, which is not so and hence which may easily imply the worst (that is, the least efficient) allocation of productive resources in society. That would mean the end alas of all the touted virtues of capitalism.

At the macro-economic level, this is reflected by changes in the nature of business cycles. What used to be more or less regular industrial cycles (of essentially the Juglar type) or modifications thereof is now replaced completely by irregular bubble-and-bust cycles, reflecting the changeable “moods” of casino capital. If the latter sees no or little speculative opportunity, the capital market finds itself in a protracted depression, which involves a state of radical liquidity trap, which is characterized by the coexistence of abundant idle money (inconvertible into capital) with scant active money (to buy and circulate commodities), the exact opposite of hyper-inflation. Since casino capital can always wait, however, there is no automatic cure to this state in the market. Only when the central government manages to lure casino capital into investing in a preselected field of industry that appears to be sufficiently promising, does investible idle money return to the capital market, inflaming passions which may lead to a bubble. The latter, however, will soon be out of breath as over-indebtedness in the economy becomes excessive, until it suddenly comes to an abrupt halt in a “hard-landing” with immense casualties, and fraught with the bitter aftertaste of fraudulence and deception that are always discovered just a little too late. Some artificially engineered bubbles, such as the IT bubble, involved some salutary economic effect in promoting the application of the information-and-communications technology (ICT) to industries, and thus massively elevating their productivities. However, there are far less commendable instances as well, such as the more recent housing bubble, which amounted to little more than the misuse of the obscure method of securitization to swindle subprime borrowers to their ruin. In either case, the government must have depended on the “cooperation” of casino capital which, for its part, has no inclination for itself to serve the public cause. For example, it habitually undermines welfare states by evading taxes, which it can do by simply operating on a “global” stage. That is to say, it can always hide in the anonymity of the fiscal paradise (the colourful French expression for “tax havens”), while awaiting the next chance to “make a killing” by wreaking havoc in some normally quiet and calm capital markets. Since the post-bourgeois nation-state has for years been weakened and impoverished by neo-conservatism à la Reagan and Thatcher which has left it with a dwindling tax base, it must rely on willing cooperation of casino capital to boost the economy. However, financial interests always retain the upper hand over the nation-state. Indeed, the former are not likely to act to suit the latter’s needs, while the reverse is more likely to be the case. That inclines me to believe that the continued dominance of casino capital in the contemporary economy must lead in the end to the demolition of the welfare state. That undoubtedly is contrary to the interest of human society, and so this trend must be terminated as soon as possible by the emergence of a new society.

What strikes me as most noteworthy in this connection is that the bubble-and-bust cycles in today’s world economy possess none of the regularity of capitalist business cycles. There is, in particular, no clearly discernible sub-phase of average activity between the ones of recovery and of overheating in its prosperity phase. That would mean in turn that there is no space in which the law of average profit (the law of value as it appears in the capitalist market) enforces itself in the present-day economy, since the point at which the demand for and the supply of labour-power tend to be equalized cannot be identified. If the value of labour-power thus remains indeterminate, so are the values of other commodities. An economy in which neither the law of population nor that of value can operate does not deserve the name of capitalism, which is another way of saying that the ultimate disintegration of capitalism is now quite imminent.

8b) You have also said that bourgeois economics talks nowadays much about “money” but possesses no credible theory of money. In what way do you think that its theory of money is faulty?